I have just finished a truly extraordinary pilgrimage on the Camino de Santiago and cannot wait to write a post or two or three about it, but I am still in Spain and May 9 is coming up so I am reposting this one from a few years ago. I felt Geoff’s spirit with me all the way, carrying me along, pushing me up hills, consoling me as I walked the exhausted last miles of the day, sat with my husband on a most unexpected trip to the Santiago hospital. How lucky am I to continue to not only survive but thrive these 36 years after his death. Buen Camino, my dearest son, wherever you are. I am full of love and gratitude.

I was going to tell you about the great Zoom re-creation of my women’s writing group last Sunday, when seven of us joined for the day to express in words the many feelings and thoughts prompted by poems I shared, but I’m not going to do that.

I debated writing about the powerful virtual mindfulness retreat I sat (in front of my computer) last week, given by renowned meditation teachers Joseph Goldstein and Sharon Salzburg to 2300 others all over the world. I thought I’d quote Ajahn Chah, Thai meditation master, who said “Anything that is irritating you is your teacher,” thinking it a rich source of reflection for the constant challenge, destabilization and disruption we are all feeling daily—but I just couldn’t get there.

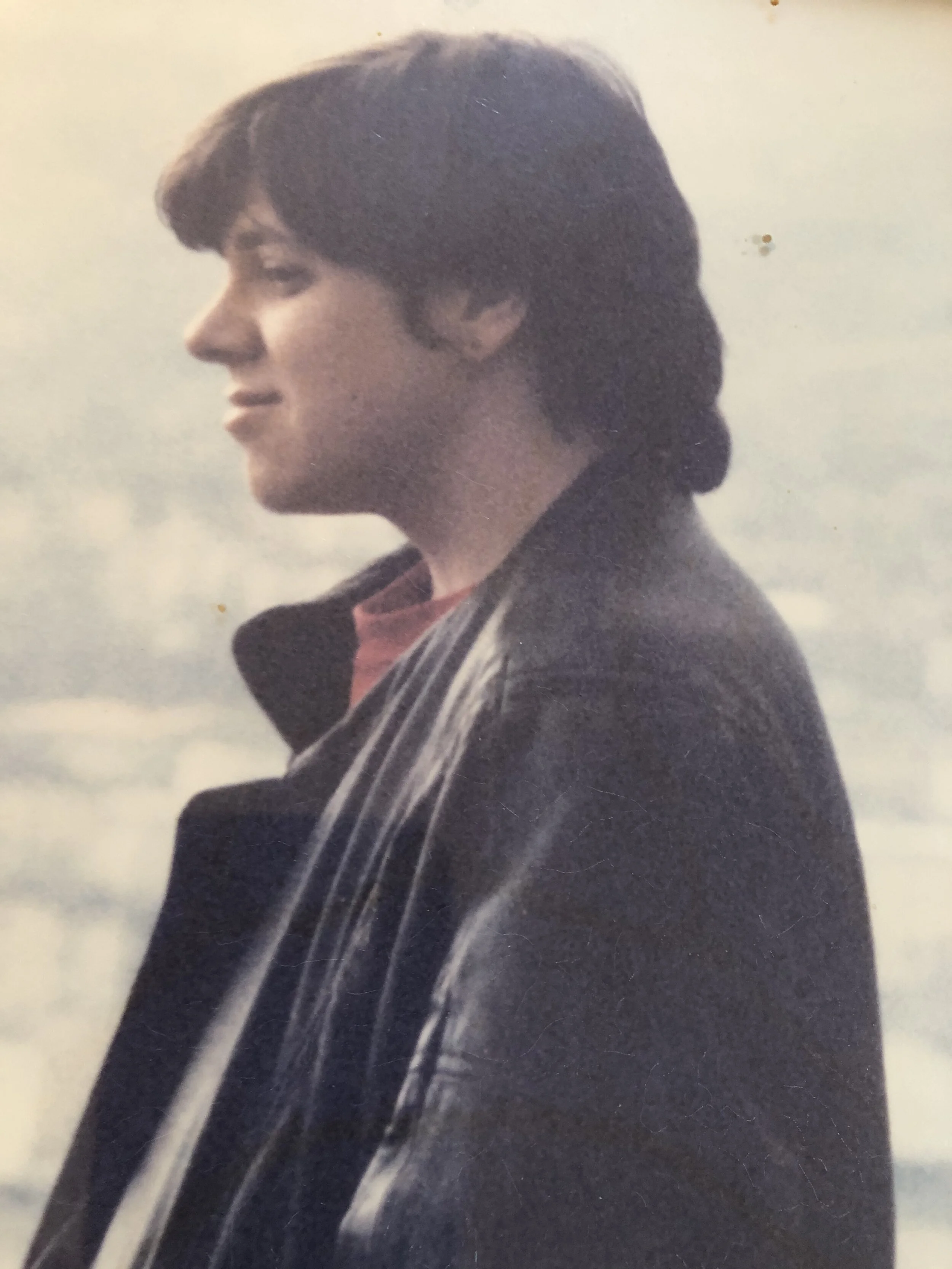

Because, as my son’s beloved teacher said many years ago, introducing me to a group of students at the Trinity College/Rome campus where Geoff spent his junior year abroad, “T. S. Eliot was wrong. The cruelest month is not April, but May, the month Sharon’s son Geoff died from a late night fall from the wall along the Tiber River.”

May has again arrived, and the torment of remembering him, his death, his life, has hijacked my mind and heart.

OUTLIVING HIM

for Geoffrey

His ghost blooms with the lilacs--

nothing takes away May’s missing him,

not the bluebirds his father’s enticed

at last to our backyard

not the ravenous red tulips

or the luminous acres of lawn.

He brings death to the newly born.

It’s not that I forget him in winter.

but winter’s flowers are underground,

sheltered by hard earth--

not the outrageous bursts of spring

I cannot hide from.

His death day sounds its arrival

with dogwood and daffodils

while I, now gray haired and lined,

survive at winter’s edge

unwilling still to outlive him.

(Four Trees Down from Ponte Sisto, 2006, Dallas Community Poets Press)

The anniversary of his death is this Saturday, May 9, the day before Mother’s Day, a day always for me, of tangled emotions. Those of you who have lost people in your life you’ve deeply loved will recognize the memorial surprises of unexpected choking sobs, of darkening moods, of sudden sore throats, chills or headaches that arrive with unerring precision during these anniversary weeks.

It’s been thirty-three years since my son died alone on that dark night in Rome, his death still an unsolved mystery, and the raw chasm of grief it left still surges unannounced. Struggling to find the words for ideas I’d thought to write about this week, deleting everything I began, I realized that his death was my story, that honoring his memory was the only way to get something on the page.

Just this morning, someone I hadn’t seen or spoken to in years asked the question that always comes when someone hears that death has punctured one’s life. It’s such a complex question for me to answer that ten years ago I wrote this poem:

THE STORY

we’re sitting around a table eating lasagna, or walking down a dirt road in Virginia, maybe in a dusty country store crammed with jams and tee shirts and vitamins, or possibly in the back seat of a taxi in New York or a hotel conference room or next to each other on a plane—when the question comes---how many children do you have and I tell the person that I have two but one is dead and see the look I already know I will see---a kind of blanching—a pulling away or maybe back from what they hadn’t wanted to hear and my god I hadn’t wanted to hear it either but now it’s like this unlit candle I carry around never knowing who will have the match and then they say how did your son die—of course you don’t have to say if you don’t want to-- and of course I don’t want to but I do want to and I tell them the story—a little bit—he fell fifty feet from a wall in Rome but then of course they will think it was suicide---which of course is not true--if I don’t tell the rest of the story—how thrilled he was to be a student in Rome—his asthma—the dinner with John—the paparazzi—the branch in his hand—and their eyes are so kind now---they are so full of happiness that their own children are alive—and then they want to know how long ago and I tell them it’s been twenty three years already—he’s been dead longer than he was alive—only twenty one I tell them—although he really wasn’t quite twenty one but it’s easier to say he was and sometimes like today I start to sob surprising myself and causing the other person to back away or hug me and try to comfort me and it doesn’t do any good really because the hole is so big and there’s no way to fill it my god I have tried and tried and will probably try forever and then the conversation turns to what someone’s husband does---what book they are reading—maybe what school their child goes to—because after all we are all trying to tell our stories aren’t we—and I smile and listen and all these candles are burning inside me and even though it’s been so long—you should be over it—I don’t know how to put them out—

New Delta Review, Vol. 27, 2010

I’ve written and written about his death. Six collections of poetry, and now I Am Not A Juvenile Delinquent, my memoir about how I’ve survived it by working as a volunteer poetry teacher at a facility for delinquent girls, despite the fact that that was never my intention in beginning the ten-year program I describe in the upcoming book (Mango Publishing, June 16, 2020). “Writing is a way to transform trauma,” I told the girls—a way to get the inchoate, the unbearable, gone from where it can daily eat you alive, a way to reach and connect with others who’ve suffered in similar ways. I brought them to classrooms, cafes, galleries, The Hotchkiss School, and our yearly poetry festivals, where their passionate, powerful voices reached and affected so many. I hope you’ll all read my book so you can hear those voices too. They are rich and strong and brave. Geoff would have loved them, sensitive creative artist that he was.

For a minute, I let myself think, what, who would he be today, at almost 54? Would he have a wife, children, cousins for my grandsons, be the brother whose death didn’t make Matthew an only child? Would he have followed his creative dreams, or had his tender soul squashed by the harshness of today’s world? But I don’t go far with these thoughts, which always lead to painful dead ends.

Instead, I bring to mind the words I spent a year searching for, to have inscribed on his gravestone, carved deep into rough Westerly granite.

And think not you can direct the course of love

for love, if it finds you worthy, will direct your course.

Khalil Gibran, The Prophet

I draw in afresh the comfort and wisdom of those words, their rightness radiant when I found them at last. They remind me again that love, my love for him, for my living son’s family, for my husband, for the girls, for all of you, and this hurting world we’re inhabiting now, keeps directing the course of my life.

But all those candles are still burning inside of me….

May 6, 2020